When I was an anarchist-punk-looking-atheist-feminist teenager, I started to attend the sermons of a priest. The audience mainly consisted of 60-90 years old women, a few elderly men of similar age – and the three of us, 16 years old girls. I did not become religious, I had no intention to turn to the Church for salvation. I went, simply, because a very good friend recommended that this particular priest – as someone worth to listen to. His name was Jóska Farkas.

Having been born with a critical frame of mind, I found very few people in my life I wanted to listen to – but I immediately realised it was worth listening to Jóska Farkas. His sermons were more like lectures, examining a different topic every Sunday morning. The venue was a simple hall in an ordinary building. There were about 200 people in the audience, and you could hardly find an empty chair.

The very first time I went to his sermons-lectures he talked about the misery money brings, and somehow he moved to the topic of illness. He said – and I had never heard this idea before in my life – that “we were responsible for our illnesses”.

I felt shocked and first I just wanted to disprove him. He did not say much about the subject, but I became pre-occupied with trying to find reasons why may be right or wrong. Initially I felt angry with him, feeling he was blaming the innocent victims of illnesses. At the same time I sensed that his ideas represented another level of reflection, which I wanted to understand. I knew he did not mean to blame, instead he wanted to wake up a total sense of responsibility for our life. This was a new challenge for me.

A few years later I started to take a Hungarian version of the contraception pill, which had heavy side-effects. First it stopped my period for several months, then I started to bleed continuously for about six months. The doctors claimed there was nothing wrong with the pill, but when I discontinued taking it the problems disappeared. During the months when I was continuously bleeding I had a feeling that I “wanted” to bleed. I was in a relationship with a man whom I did not really like. I realised, my constant bleeding problems was useful, and with the real excuse of the bleeding I could avoid his daily advances. I was suspicious of this thinking, but the idea was playing in my head, although I think I have never mentioned it to anyone those days.

After I emigrated to England in 1978 I visited several communes, searching for one I could move into. I discovered a commune, which was established on the West Coast of Ireland in the beautiful and wild Donegal. I read a few books by people who moved there, and later I visited them. This commune called Atlantis, was led by two sisters. In a biographical book written by one of them, I found a letter she wrote years earlier. She mentioned on-going menstrual bleeding – which she interpreted as a protest against her terrible marriage. She said that doctors tried every method to stop it, which were often potentially dangerous. She finally decided that enough was enough from the medical profession. She started to heal herself, and I remember her words: “I will do it in my own way”. It worked. I had no idea what “her own way was” – but I could feel the determination, which, for sure, can lead to recovery. She left her husband, joined the commune, and soon became a flowering and assertive woman. She looked very happy and healthy when I met her years later.

I also had an American hippie friend who used to live in London in the 80’s. He used to visit me bringing me large bags of brown rice and chickpeas, in his attempt to turn me into a vegetarian. He told me his mother had cancer. One day he received a letter from her. She wrote to him that she still had not recovered from her cancer, because, she wrote: she “realised she still had some interest in being ill”.

Later on in my Social Work and Social Policy MSc studies at the LSE I learned about the ‘sick role’. A role which society can force on people, but people can also chose to have, even when they have recovered from an illness. In the professional literature the question has been raised whether people with mental health problems “should have” the ‘sick role’, and whether it would lead to privileges they “do not deserve”. Or whether it is a useful role enabling them to take it easy as a sick person should, at the same time forcing them to think about themselves as “needing” treatment, needing doctors to make them feel better. We also learned about the ‘impaired role’ – which is a bit like a disability, it is not sickness because it might be permanent, it refers to a lack of ability to function as average ‘normal’ people do. The University course encouraged us Social Work students, to perceive our clients (who had mental health problems) as fitting into this ‘impaired role’ category. The so called ‘normalisation theory’ prescribes, that you aim to achieve an acceptance of this ‘impaired role’, but you try to offer for the ‘impaired’ people as ‘normal’ life-style as possible. For example average housing, training, jobs, entertainment. No segregation and no large institutions, no asylums and no specialist training establishment. ‘Integration’ while respecting their ‘difference’. For example a Carer with this attitude would encourage the ‘patient’ to take up adult education courses, studying together with the ‘normal’ people, but perhaps offering extra support. However, the same Carers would be expected to ensure that the people with mental health problems take their medication, see the psychiatrists. Any attempt to discontinue with the mediation or avoidance of seeing the ‘mental health professionals’ would be interpreted as ‘lack of insight’ and perhaps a sign of the psychiatric illness itself. “Choosing to be be mad, instead of wanting to become normal”.

I always suspected that the above taught-learnt categories were not only patronising, but they were based on superficial thinking. The acceptable and fashionable terminology makes our thinking shallow.

The whole question of “Do we choose our illnesses?” – raises other questions:

What do we mean by ‘choice’ in the first place?

How do our choices relate to our ‘free will’?

What is the relationship of our consciousness and the unconscious choices/decisions?

If it is true that a psychological need inside us, which we are NOT conscious of, makes us ‘choose’ to become ill – then should we call it a ‘choice’? Is it a choice if the process is more like a determining need forcing something on us, which we can’t fight as we are not even aware of? We have no ‘free will’ to fight it, or to agree to it. So, if it is a sub-conscious psychological need (e.g. the suppressed desire to be looked after) which forces us to develop a certain illness, then we can’t say we choose it, we can’t argue that we are responsible for the illness, or that consciously we could stop being ill.

Believers of the psycho-dynamic thinking might argue that once those unconscious wishes have been made conscious (have been ‘interpreted’), the need for the illness might disappear. So we could say, that our psyche ‘chooses’ the illness, or leads to the physical organism to become sick, but not ‘us’, not our conscious self.

The question still remains, why some of us have asthma, others have flu, ear-ache, a measles, eczema, cancer, ulcer or migraine? – Why this illness and not another?

Apart from straightforward biological or genetic explanation, there is also a way to see the illness as a symbol. For example, years ago I had a mysterious illness, which attacked my feet. When I began to think about the reasons and the ‘meaning’ of the condition, I started to play with the idea of my illness symbolising my general life-problem of that time: I wanted to stand on my own feet, but I could not. I was living with a man, who did not let me to be independent and I started to depend on him against my wishes. – This might be far-fetched, but not completely impossible. I also always had a feeling, that I would never develop cancer, because, I believe (I don’t know on what basis) that people who develop cancer are unable to express their anger. They bottle up their negative feelings and somehow this creates the cancer. And I do know how to express anger.

So, my priest was not right. Neither my lecturers at LSE, who only managed to conceptualise a banality any school child knows, who wants to avoid the exam day in school. They develop ‘sick-role’. In my opinion when they talk about the ‘impaired’ model they are just expressing their pessimism about people who have mental health problems. Perhaps because, as professionals they don’t want to admit that they don’t have a clue how to help these people! So they think about them as ‘in-curable’! How do they dare!

However much we might ‘benefit’ from the ‘sick-role’, we also have so much to loose whenever we become really ill. So it can not be in our real interest to become, and especially to stay ill on the long run. If someone has a depressive mentality and they are giving up on living, then perhaps, it is natural if they become ill and they don’t wish to recover. I am certain, that if not the first development of illness, but the maintenance of it, is very often in our hands, and it depends to large degree on our will-power, our mentality, our general life-energy. And on our libido. No one with a healthy libido want to stay ill for a long time. People who really want to live, and live fully, will do everything to recover, and their own positive vibes will help with their own recovery. More than that, they will have a positive and healthy effect on their environment.

If it is possible that we are not responsible for our illnesses, then we could try some religious arguments. Perhaps God makes us ill. As a punishment for our sins. The problem is, that I am still not religious and I don’t believe in God. However I do believe in Fate. I also believe that nothing is accidental. I don’t know if God, or Fate, or Nature is punishing anyone through throwing an illness at the person, but I think that sometimes illness does have some connection with punishment. People can punish themselves, and can try to punish their loved ones through illness. “I have been smoking so I had been punished with lung-cancer”; “I have been over-eating, so I only deserve that I became sick” – I have heard these kind of statements many times. I have also seen people THROW the fact of an illness against someone whom they ‘love’: “you bastard, can’t you see that I am ill!” As if it deserved respect and gave you rights, so it becomes a weapon to hit a partner’s head with. If you don’t feel pathetic because of your illness, you might as well feel superior, proud, and put other people in their place, because they lack the special status of: “I have diabetics”, “I have ulcer”, “I have cancer”, “I have HIV”…

The more fatal the illness is perceived, the more it can be used as a weapon to make demands. It is difficult to make demands with obscure or complicated illnesses when the person feels very unwell, but the doctors are unable to give a diagnoses. These people suffer from the uncertainty about the nature of their illness, plus the lack of social recognition. They may be very ill, but society is not giving them the sick-role and the automatic privileges which sick people often get.

There are “respectable” illnesses in any given society, and respectable treatment methods, and the two need to be synchronized. If someone with HIV only goes to a Herbalist, some may turn against them and believe that they are responsible for the continuation of their illness, and they are irresponsible ultimately. The original sympathy may turn to hostility.

Although I am not religious (I keep saying), however, during the last few decades several events happened, which made me think that someone or something (Fate?) is playing games with us. A few people I know and deeply respect had been made ill by this “Fate”.

My hypothesis is that these people “are being put on a trial”. These people are very special. They are not the depressed type, they are the type who want to live, who are full with life-energy, they are beautiful, attractive people. Some other people I know who also have a very healthy and life-giving side to them were born with severe disabilities, or as children developed chronic problems. Despite their disability or serious illness they radiate life-energy.

The biggest shock was when I discovered what happened to M. I met her at college in 1989 when she was about 24 years old. At first I slightly disliked her because she was blond and just too beautiful. I think I was simply jealous of her. It took me a week to realise that I always agreed with the things she said (a rare experience) and that I generally liked her. She told us she loved travelling and she had already been to Africa and to other parts of the world, but still there were many other countries she wanted to go to. Later when she went to the States, she accidentally turned up in a gathering of Indians who welcomed her, and even asked her to speak. I kept in touch with M. and used to visit her regularly. A few years later I phoned her sister, telling her that M. had not answered the phone for weeks. Her sister asked me to sit down while she was telling me the news: M. was paralysed, from chest down. She told me, no doctors could explain the reason, but they thought a mysterious virus attacked her – although no one else in her environment got ill apart from her. The doctors thought she had no chance of ever starting to walk again. Soon afterwards I visited M. in a specialist spine-injury hospital, where she seemed to be in good spirit. She told me at the beginning she was very depressed, but now she was ready to face life. That time, for several personal reasons I was in a depressed mood. When I saw M. smiling in the hospital I felt so ashamed for my depression. Just a few months after becoming paralysed she was already in a positive emotional state. She was lovely, bright and joking, while I looked miserable, although I had no comparable problems in my life. She was still giving so much warm and love to several people around her, I had to admit to myself, she gave me energy, and I felt it should have been the other way round. Later she was given a ground-floor flat which was adopted to a wheelchair. She made the flat beautiful in no time, bright, colourful and cosy. She started to play basketball; organised a dance-theatre in which she was also performing. She also kept her part-time job in London, 100 miles away from her home-town, she drove up to London 2-3 times per week. Now she is working in a university nearer her home. Unfortunately she has not became better physically, but she never complains about her disability, and she has much more friends and a more active and constructive life than anyone else I have ever met.

A 75 years old woman from North England also surprised me when I met her a few years ago in the Union’s ‘Convalescence Home’. We were sitting at the same dinner table and we started to like each other from day one. She told me many funny stories from her life. She was taking the Mickey out of everyone – including myself. She told me, years earlier she started a ‘remittance’ group for the local elderly but she was getting bored with them because all they ever wanted to do was remembering the past, but she wanted to think about the future! One day I asked her what was the reason why she was coughing so badly. She told me she come from a small mining town and when she was young every child had some form of lung problem. No one noticed that she developed TB. As they did not treat it for long time, her lungs and spine collapsed to some degree – and she is very-very tiny! For the rest of her life she has to use an oxygen machine several times a day to help her breathing. The illness forced her to give up nursing at a young age. While she was talking, she did not express any sign of bitterness about what happened to her. She talked about her childhood illness with an understanding smile, trying to express that things were different those days, I should not be upset that her parents did not notice her illness.

I only mentioned women so far. I could continue the list and as I know much more women then men who have chronic illnesses or disabilities, and they still live a full life. They don’t want the ‘sick-role’. These women don’t expect much from others, but they give lots of warm, love, understanding. They are never patronising, they don’t play the superior. Luckily I I also know some men who are similar. They usually do not consider themselves good people, and often have very high expectations of themselves, demanding more and more from their own selves. Most importantly they have refused to play the victims, and they have refused to become rejects – the role society is offering for them.

While I was travelling in India I read an article about a very special Indian-origin doctor who lives in the US. He had two heart attacks and now he is in a wheelchair. He is unable to breath through his nose and has to breath through a tube inside his throat. Years ago he was told he only had a few months left to live unless he agrees to a heart surgery, which he refused (and now the doctor who suggested the surgery agrees with his decision). He is an experienced and fast eye-surgeon and is also a plastic surgeon. Despite his condition for several months, every single year he goes to India in order to perform hundreds of free operations for poor people, e.g. clearing deformities on the face, removing cataract from the eyes. He travels to isolated rural villages and performs his free operations in a tent he and his team takes with them. When back in the States he lives on his own, does his own cooking, cleaning and housework.

When I think about these people I start to feel angry with ‘fate’, would like to scream: “There is no justice, they did not ‘deserve’ the illness or disability!” However my scream means that deep down I feel some (other) people do “deserve” to become ill or disabled. I don’t like to admit this, but yes, it is implied. In my favourite childhood book the child-witch was throwing measles-spots on people she did not like. This is similar to the idea of cursing, which, perhaps is another possibility, but I don’t want to go that far. Just want to mention, that in my opinion, if someone (especially a child or a vulnerable adult) lives with others who are against her/him, who are constantly thinking negative thoughts about her/him, who do not like her/him, who wish bad things would happen to her/him, who ‘send negative energy’ towards this person even if they don’t consciously do it, who do not pay any positive attention or look after the needs of her/him – then this child or vulnerable adult might easily become ill.

So these people I talked about don’t ‘deserve’ to have any illnesses or disabilities – in the sense, that they are brilliant, positive people, who do not want to take advantage of the ‘sick role’, they do not want to have a half-dead life and they do everything to get better. There is no way I would accept that they were ‘responsible’ for their illnesses or disabilities. Ignoring my stupid suggestion about ‘cursing’, the only reasonable explanation I have: perhaps ‘Fate’ has put them through a ‘trial’.

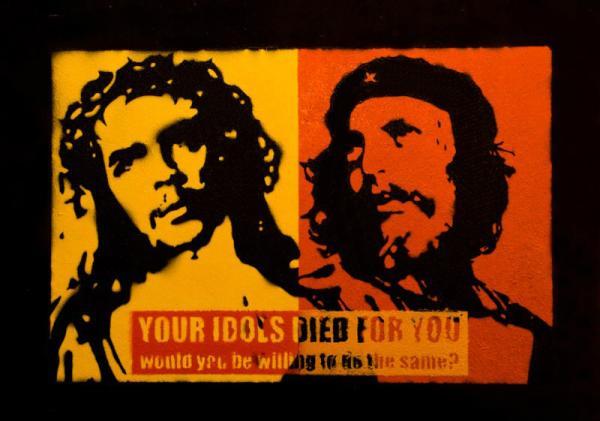

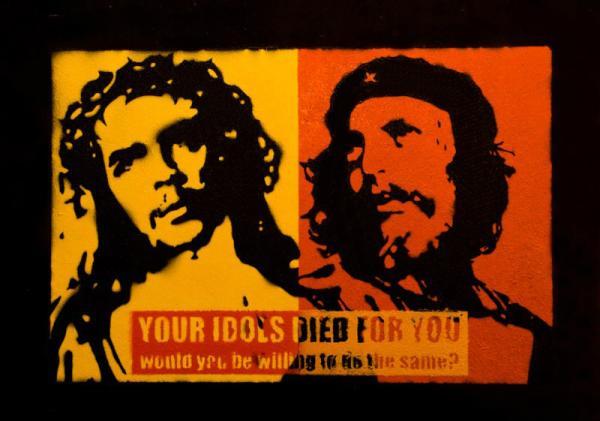

A bit like Jesus, but no one will write stories about them in the Bible. Sometimes I think the stories about how Jesus was put through this and that trial – are nothing. Clearly the bible was written by men, who have never experienced the trials most women all over the world go through nearly everyday of their life, who generally have to face and solve more difficulties than men.

In some sense, both ordinary men and women have to face trials almost on a daily basis. Just bringing up children is a series of trials; on certain days not-spitting-into-the-face of a manager might be another trial. Living far away from people you love is another trial which especially immigrants and refugees have to face. Surviving the death of people close to you is tragic trial everyone has to face one day or another.

However, some people – and I believe they are very special people – have been put through more serious trials. People often ask, when something horrible happens to them: “WHY ME?” – And I am asking the question about these people: WHY THEM? I know that not everyone would cope with the difficulties, illnesses, disabilities they have. And they did not only survive these, they coped with their often life-threatening problems in an incredible positive way. At least they coped with some aspects of it positively, because if you ask them, they would have many complaints to make about their own selves. For example M. might tell you that she is still smoking so she is not looking after her health properly. The Indian doctor might think that he should have operated even more people.

I have this crazy feeling – that the illnesses and disabilities these people experience – were somehow ‘deliberately’ thrown at them, to see, if after coping with these, they could still be as good human beings as they were before. And they stood the test. If anything, they even became better. And perhaps that is the purpose of illnesses. To give a warning to people: life is precious, you have to respect it, and to live it as fully and as positively as possible. In whatever circumstances, with whatever body you have.

The crazy idea I am suggesting therefore is this: the real function of some of these serious illnesses (and disabilities) is to ensure, that some ‘chosen’ individuals suffer without becoming inhuman and selfish. And the rest of us learn from them.

If my theory has any truth in it and if this was also the case historically, then I could suggest that perhaps the Jesus myth was invented to illustrate it. It was perhaps the summary of experiences many people had. Almost all women, and some men. It would have made more sense to put a woman on the cross, it would have reflected past and present societies and individual life experiences better. However, the hero-cults are dedicated to men, so again, we were given a man to respect on the cross, as a victim. In fact, as a victim of other men, not of women.

They twisted the story several times. They claim it was the suffering which would safe humankind. They claim it is the feeling of guilt which would purify us. But I believe this is not the case. Although it is natural to feel unhappy when something tragic happens, I believe we need to refuse to base our life on suffering and guilt. If we can achieve this, there may be less sickness in the world.